“How does it feel to be a problem?”

W.E.B DuBois asked this famous question in the seminal Souls of Black Folk in 1903. While Du Bois was specifically speaking to the experiences of Black Americans in the postbellum Jim Crow era at the start of the 20th century, perhaps we can borrow this question to frame our work as scholars, researchers, and members of developmental relationships in a sociopolitical context that is actively hostile to those who seek truth, no matter how difficult and disconcerting it might be.

It seems surreal that framing our work around reducing inequalities for young people could be considered controversial. After all, many of our institutions proclaim to enrich society through inclusion and improving life opportunities for all. Many of us come to academia strongly inspired by this mission, perhaps because education—and the relationships we inculcate on that journey—has provided us each with a new vantage point. These mottos inspire us to do the same for another generation.

We know that social progress and advancing democracy often provokes a backlash. Indeed, for many scholars , mentors, and mentees, we have been living and working in states and regions where restrictive laws limit or outright prohibit our ability to directly address diversity, equity, and inclusion in our teaching, research, and service at public institutions. Since January, we have experienced an unprecedented retrenchment of academic freedom via the government agencies that have funded so much of our research since World War II. Virtually all of the William T. Grant community, regardless of what state we work in, or institutional governance, have been impacted. This change has happened rapidly, and even if a reversal of this policy direction occurs, it will take considerable time and effort to return to its former state. The rapidity, constancy, and mean-spiritedness of the moment is demoralizing.

Learning from History

In this moment, we would be well advised to look to history for guidance. Nearly a century ago, Black educators imbued their students and community with a sense of purpose and pride through their caring and developmental relationships, instilling them with the resistance and resilience capital which would launch their own intellectual journeys. As historian Jarvis Givens writes, “The physical and intellectual acts by black teachers and students explicitly critiqued and negated white supremacy and antiblack protocols of domination, but they often did so in discreet or partially concealed fashion” (2021, p. 5). Givens terms this resistance work as fugitive pedagogy.

This was existential for the progress and future of Black Americans. As Carter G. Woodson wrote at the time, “If a race has no history, if it has no worthwhile tradition, it becomes a negligible factor in the thought of the world, and it stands in danger of being exterminated.” Givens noted that despite a dominant narrative devaluing and dismissing the accomplishments of Black Americans:

“exclusion, violence, and confinement in a land that professed the ideals of liberty and justice for all prompted a counter-historical narrative and way of knowing—indeed one represented in the extensive factual evidence contained in Carter G. Woodson’s books, which documented the wrongs done to black Americans but also their achievements and contributions to the modern world” (Givens, 2021, p. 3).

Indeed, fugitive pedagogies were deployed in classrooms, schools, and HBCUs. Rather than a retreat from advocacy and information, fugitive pedagogies were a strategy calibrated towards liberation. The work was integral in laying the foundation for further resistance work in the courts, through legislation, and policy. The seeds planted during this time inspired students in their emancipatory work a generation later.

Leaning Forward

Perhaps we can draw an analogy about our work as mentors and mentees in developmental relationships today. Mentoring and developing junior scholars is the appropriate response to the current attacks on democracy. Our presence, support for one another, and refusal to give in to totalitarian pessimism makes our work critical resistance in some of the most challenging policy environments we have encountered. Our development as researchers, teachers, and active participants in democracy necessitates relationships that span experience levels. Both mentor and mentee benefit from the exchange of ideas, strategies, techniques, and hope. Modeling relationships across identities can inspire mentoring ecosystems, where many engage in the work of supporting junior scholars; these ecosystems lessen the cultural taxation of those who willingly take on mentoring roles while providing many more support systems and network nodes for early career scholars.

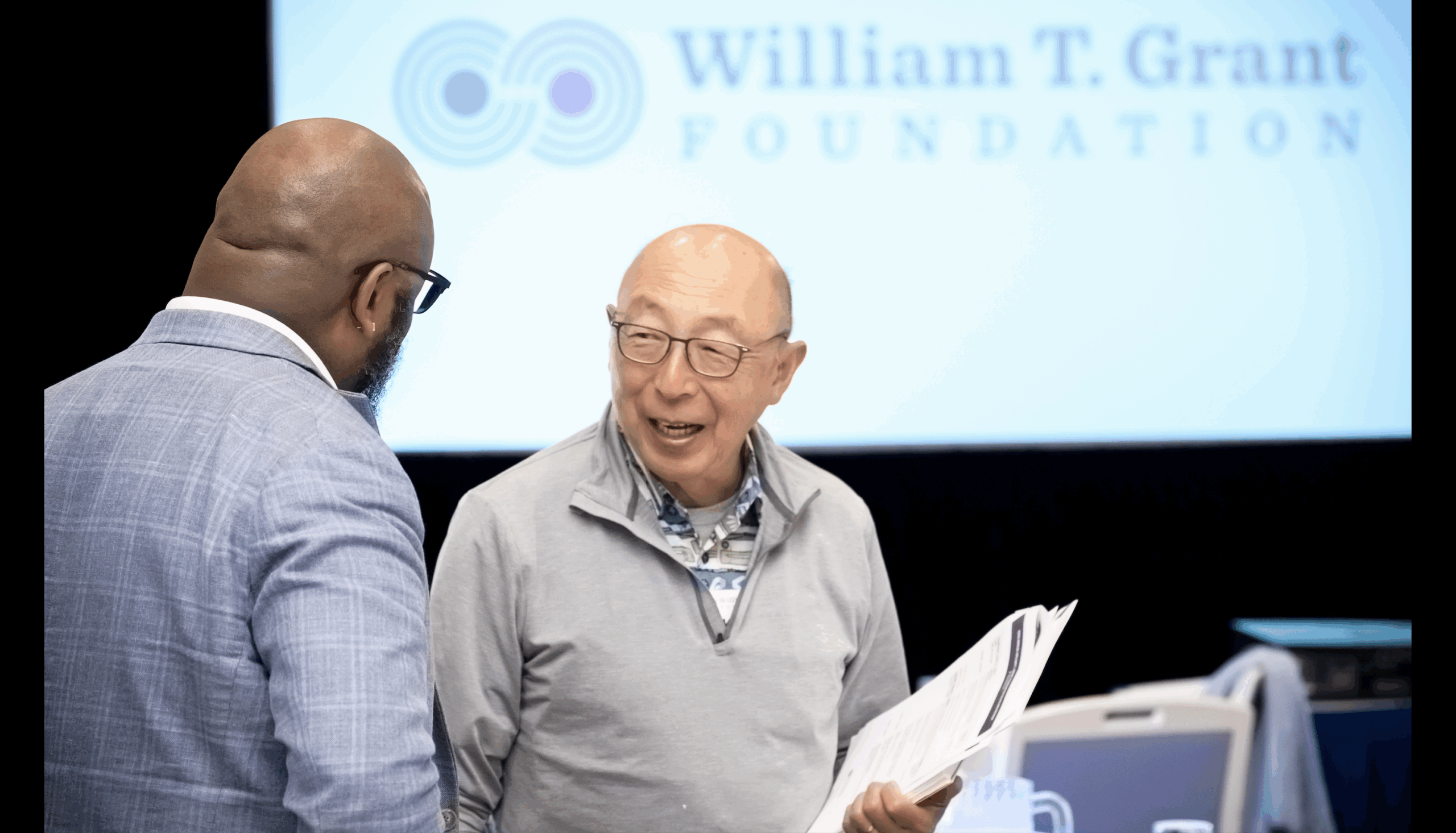

Like these relationships, I remain committed to the William T. Grant Foundation’s 20-year commitment to working with mentors and mentees to create a research community that reflects the diversity of experiences and lives of the communities we serve. Indeed, it was inspiring to me when I recently attended the Reducing Inequality Convening in Washington DC as I heard grantees and their research teams share how their work is improving educational outcomes for diverse students and communities. Our work continues, despite the headwinds because it is the work of a democracy to ensure that opportunity is not limited to those who have the benefit of being born into a wealthy family, living in a certain zip code, or not having to navigate a social reality that assigns challenges based on race, ethnicity, national origin, sexuality, ability status, and other socially consequential identities.

Mentoring and developing the next generation of researchers matters more than ever, despite the headwinds. As Maria Wisdom, assistant vice provost for faculty advancement at Duke University recently stated, “The conditions for mentoring continue to deteriorate. At the same time, there’s never been a greater need for truly impactful mentoring, and I think there has never been a moment at which it’s clear that we need to learn to support people without having all the answers.” Our resistance at this moment can come via our sincere dedication to supporting one another across generations, so we are able to meet the coming moment for rebuilding and restoring.