I’m drafting this post in January, which has been National Mentoring Month since 2002. It’s as good a time as any to reflect on the developmental networks that have advanced our professional and personal growth. Often, we think about one-on-one interactions and individuals: when I think about mentoring in popular media, the dyad comes to mind. Luke and Yoda, Miss Celie and Shug … it’s a familiar framing.

One of the most valuable aspects of these relationships is how one connection can lead to many others. The impactful mentors in my life introduced me to a network of advisors and confidantes beyond themselves. They enjoyed helping new voices in academia and recognized the chance to provide access to diverse identities and experiences beyond their own. In my own mentoring research, I have gravitated to W. Brad Johnson’s concept of “constellation mentoring,” described in my recent book, Restorative Resistance in Higher Education:

Constellation mentoring, which is often called the “board of directors” approach—just as any corporation or nonprofit has a CEO who is advised by a board, one can conceptualize their professional and academic journey as being informed by a personal board of directors. (p. 44)

My mentors willingly shared their “mentoring contacts list” with me. While we tend to emphasize our mentors as those who unlock opportunities, in many instances, what the mentor actually did was provide access and legitimacy to others—expanding our network and nurturing well beyond that individual’s reach. For example, my first graduate school mentor, the late Dr. Charles Willie, invited me to a research group to investigate the impact of HBCUs in the 21st century. Our research team published a book, The Black College Mystique, and among our consultative group was Dr. Jim Honan, a leader in Harvard’s professional education programs. That connection led to many other interactions—today, Jim and I co-chair the Institute for Educational Management, one of the leading higher education professional development convenings in the country. It’s very possible that Jim and I would have found each other as fellow higher education researchers, but Dr. Willie’s willingness to bring us all together created the conditions that impacts our professional development to the present day.

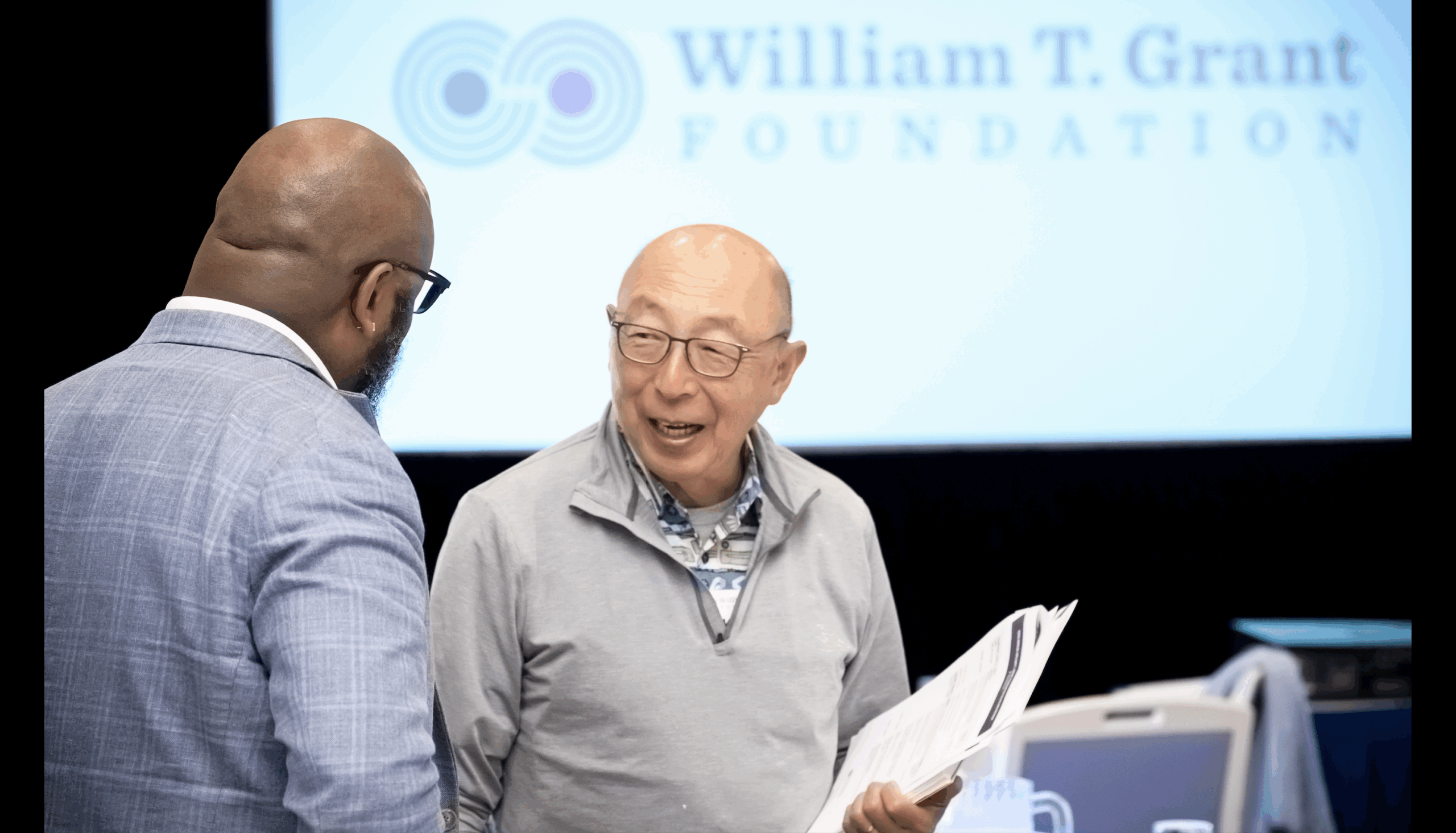

Even my work with the William T. Grant Foundation is due to another mentor’s generosity. I was fortunate to have Dr. Vivian Louie as a member of my dissertation committee. Our relationship continued after I graduated and led to an opportunity to attend a William T. Grant convening. Vivian later co-authored a report with Alicia Wilson-Ahlstrom citing research I conducted with Veronica Jones as a William T. Grant awardee on mentoring for junior scholars of color. I think of Vivian as a bridge builder who graciously invited me to be part of this incredible organization that is invested in the power of mentorship in word and deed.

As a mentor and/or a mentee—I hope this post inspires you to reflect on how your dyadic relationship is an extension to truly building a larger network for your partner in the relationship. Strong mentoring relationships are not dependent on being the “sole” source of assistance and guidance; rather, they thrive by providing introductions and affirmation to both partners. This leads to reciprocal, mutually beneficial relationships that have multiplicative impact. Having hospitable harbors to refine and receive constructive feedback leads to our ultimate goal. More specifically, to reduce inequality in youth outcomes, we must champion and support the innovative research that scholars develop toward this end.

A valuable exercise for mentors and mentees is to ask, “Who’s on your board of directors, and who would you like to have in your constellation?” The answer may come from your dyadic partner, who can provide a welcome and warm endorsement to that missing piece of your mentoring puzzle. And certainly, it can aid in reducing issues such as cultural taxation, where underrepresented scholars have greater responsibilities and workloads in part because of their support for similarly marginalized communities. Think about your dyad as a nucleus that can lead to networks that enhance your research agenda, your career pursuits, and your life.