February 21, 2024

Social science research can yield better outcomes for children when it is used in policy, guidance, and resource allocation (Gamoran, 2014).1 It is perhaps because of this demonstrated ability that we are now seeing a proliferation of strategies for encouraging such use. But few of these strategies fully leverage ideas and findings from studies on the contexts and conditions of research use. In turn, the potential of social science research to boost policy prospects and system redesign and improvements that could help youth thrive is stymied.

Three actions are needed to bolster strategies for research use and address a heretofore missed opportunity to do better by children:

- First, strategies to improve the use of research evidence need to incorporate what we already know from studies that shed light on conditions that nurture the use of ideas and findings from research (Bogenschneider, 2021; Cooke et al., 2023; DuMont, 2015; Dunn et al., 2023; Gitomer & Crouse, 2019; Tseng, 2022).

- Second, strategies to improve the use of research evidence need to attend to the operating context, i.e., designing approaches that navigate, leverage, and compensate for the existing capacities, routines, actors, resources, and politics affecting a system (Chorpita & Daleiden, 2014; Coburn et al., 2020; Crowley et al., 2021b; Doucet, 2021; Farrell et al., 2018; Gándara et al., 2017; Metz et al., 2022; Neal & Neal, 2019; Ozer et al., 2020; Scott et al., 2017; Shirrell et al., 2023; Weber et al., 2023).

- Third, strategies to improve the use of research evidence need to be mindful of the underlying conditions that affect what research ideas are funded, how the research is conducted, who conducts the research, the assumptions undergirding the call for proposals and research questions, and who is likely to benefit or be harmed if research is used (Chicago Beyond, 2019; Doucet, 2019; DuMont, 2024; Jackson et al., 2024; Kirkland, 2019; Michener, 2019; Miranda Samuels, 2022; Welsh, 2023).

Beyond attending to the above contexts and conditions, researchers, advocates, and communicators must also respect the multiple forms of evidence and expertise necessary to provide consequential insights about how all children, families, and communities can thrive. Out of this more comprehensive perspective, strategies that improve research use will grow. Anticipating this growth, our Foundation welcomes studies of whether these strategies improve research use and unlock the potential of ideas, findings, and tools from research to ultimately benefit children.

This essay offers observations from studies the William T. Grant Foundation has supported to identify, build, and test strategies for doing more with what we know from research, the ultimate goal of which is to do better by children. The essay is presented in four parts. In the first section, I illustrate the potential of research evidence to improve circumstances in which children develop. The second section offers an interlude to briefly comment on research use. In the third section, I provide a glimpse of what we know about conditions that shape research use. The fourth section urges researchers to actively study strategies that attend to these varied conditions as they strive to encourage the use of research to do better by children.

Part 1. An Illustration: The Potential of Research to Inform a Better Economic Future for Youth

Our Foundation defines research evidence as a type of evidence derived from studies that apply systematic methods and analyses to address predefined questions or hypotheses. We see research evidence as contributing to a broader system of knowledge. At the same time, we acknowledge that peer-reviewed research is not the sole authority on knowledge and that different traditions of knowing, different forms of expertise, and different ways of generating research have long been devalued and disregarded (Chicago Beyond, 2019; Doucet, 2019; Gleeson et al., 2023; Mihalec-Adkins et al., 2023; Ozer et al., 2020).

Knowledge from research, when used with a range of other types of evidence and expertise, has something to offer decision-makers as they work to understand and appreciate the contours of their policy and service landscape. Consider the following example:

A Roadmap to Reducing Child Poverty, by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2019), summarized economic research and developmental science to inform decision-makers on ways to cut child poverty in half in ten years:

“A wealth of evidence suggests that a lack of adequate family economic resources compromises children’s ability to grow and achieve success in adulthood, hurting them and the broader society as well. … The Committee on Building an Agenda to Reduce the Number of Children in Poverty by Half in 10 Years (hereafter, the committee) has completed a review of the research literature and its own commissioned analyses to answer some of the most important questions surrounding child poverty and its eradication in the United States. Moreover, the committee was able to formulate two program and policy packages, described below, that meet the 50 percent poverty-reduction goals while at the same time increasing employment among low-income families.”

Qualitative inquiry can complement high-level trends like those noted above with research evidence informed by lived experience. For instance, research with families who have used benefits can provide important insights for designing policy implementation and its guidance. The following examples illustrate such insights, with regard to a broad swath of benefits:

From Carolyn Barnes (2021), “‘It takes a while to get used to’: The costs of redeeming public benefits:”

“This (qualitative analysis) identified … three broad categories of third-party variation that can raise redemption costs for beneficiaries: variation in the selection of eligible benefits and services, variation in how agents interact with or treat beneficiaries, and variation in the agent’s compliance with redemption guidelines. … Administrative burden scholars should reexamine policy goals and chains of implementation with an eye to barriers that may occur outside of service-seeking bureaucratic encounters. Considering multiple agents in policy delivery may help explain negative policy outcomes.”

From Mooney et al. (2023), “Experiences of distress and gaps in government safety net supports among parents and young children during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study:”

“With regard to pandemic program expansions, the vast majority expressed that food support, like increases to SNAP benefits and the availability of free school meals for pick up, alleviated the increase in food-related expenses with children home during the day…(and) recounted positive experiences with obtaining supports through their schools, particularly because community colleges offered one-stop-shops to access a range of services and aid from CalWORKs and other programs, through one responsive counselor in an otherwise fractionated safety net system.”

Together, these different streams of research are instructive to the structure of policies to reduce child poverty in an enduring way, the nature of the policy guidance, and the accessibility and stability of resource flow. Drawing on knowledge from research is what our Foundation and others refer to as use of research evidence.

Part 2. An Interlude: Further Comment on the Use of Research Evidence

Research is used in a multitude of ways to drive at better outcomes for children (Bogenschneider et al., 2019), but this essay primarily discusses two types of research use: conceptual and instrumental.

The conceptual use of research evidence (Farrell & Coburn, 2016; Weiss, 1977; Yanovitzky & Weber, 2020) can add nuance to decision-makers’ understanding of the how, why, and what of an issue. It can shift ideas, challenge assumptions, reveal new insights, or inform alternative frameworks. For example, ideas from Barnes’ (2020) broader body of research were used in an Office of Management and Budget memo (2022) that proposed strategies for reducing administrative burdens in public benefit receipt. The memo’s framing includes a conceptual category to help inform the construction of benefit guidance entitled “redemption costs,” which involves a range of resources to navigate third-party agents or vendors. This type of conceptual use holds promise for improving benefit receipt and child outcomes.

Research can also be used instrumentally (Conaway 2020; Palinkas et al., 2016; Penuel et al., 2017) and be applied to solve a problem, allocate fiscal resources, make a decision, and contribute to a specific improvement effort or plan of action. The enactment of the expanded Child Tax Credit during the pandemic is an example of an instrumental use of research wherein a pattern of findings from studies that demonstrated the ability of the Child Tax Credit was adopted to improve families’ economic circumstances. As outlined in a report from the United States Joint Economic Committee (2022), these critical policy shifts demonstrated the potential of a research informed plan to make a difference:

“The child poverty rate was cut almost in half from the previous year’s rate of 9.7%. This drop was the largest single-year decline in child poverty on record and was driven primarily by the expanded Child Tax Credit (CTC) included in the American Rescue Plan.”

However, while research use in both policy and implementation is often intended to forge a path toward better child outcomes, what research is used, how that research is used, and who uses it makes a difference to who ultimately benefits or is harmed by research (Doucet, 2019; Kirkland, 2019; Miranda Samuels, 2022; Rickinson et al., 2024). Further, research use does not happen easily or in a vacuum. Rather, and as is easily observed with many strategic uses of research evidence (Scott et al., 2017), intentional, choreographed strategies are required to improve engagement with the full range of what we know from research so that it contributes to better outcomes. Because of the challenges, potential harms, and potential for gains, it is essential that we study how strategies designed to promote routine and beneficial use of research fare and to what end.

Researchers have made considerable strides in measuring research use (Gitomer & Crouse, 2019): it can be observed in meetings (Farrell & Coburn, 2016), seen in written documents and media (Yanovitzky & Weber, 2018), heard in conversation (Asen et al., 2013), self-reported and group-assessed (Rickinson et al., 2023), and surveyed (Palinkas et al., 2016). Prior studies of ways that research is acquired and used offer ideas about how to move forward.

Part 3. An Overview: The Literature on Underlying, Operational, and Nurturing Conditions that Support and Obstruct Research Use

For nearly fifty years, researchers around the globe and in different policy spaces have systematically investigated conditions that support and obstruct the use of ideas and findings from research. We already know much from this work (Boaz et al., 2019; Chuang et al., 2023; Cooke et al., 2023; DuMont, 2015; DuMont, 2019; Dunn et al., 2023; Georgalakasis & Siregar, 2023; Gitomer & Crouse, 2019; Holmes et al., 2016; Langer et al., 2016; Neal et al., 2018a; Oliver et al., 2014; Rickinson, 2024; Sharples, 2017; Tseng, 2012; Tseng, 2022).

Most of the studies our Foundation has supported examine research use in federal, state, and local policymaking processes and in the implementation of the policy at the state and local levels. These studies investigate questions about research use in K-12 education, family economic well-being, child welfare, and mental health domains. A handful of studies have examined research use in other policy areas, including the courts, higher education, public health, and justice. These studies have ranged from documenting how professionals and decision-makers in different roles and settings define research evidence and use it (Asen et al., 2013; Barnes et al., 2013; Bogenschneider & Corbett, 2021; Mosley & Gibson, 2017; Neal et al., 2018b) to examinations of how power, politics, and partnerships affect research use (Finnigan, 2023; Gándara et al., 2017; Marin et al., 2018; Reckhow et al., 2021; Scott et al., 2017).

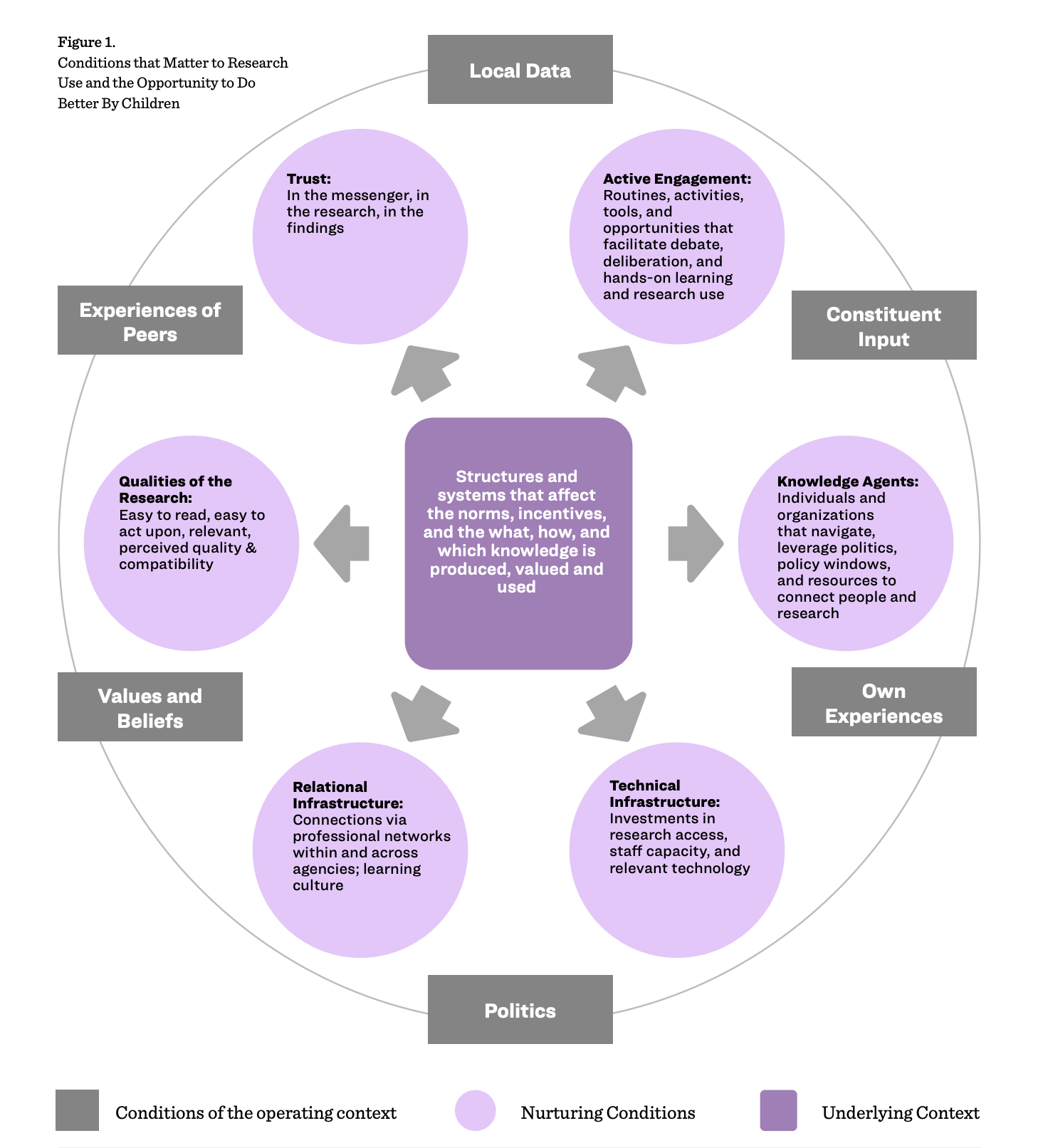

Figure 1 provides a framework for organizing recent findings about conditions associated with research use. My aim here is to briefly demonstrate that we are ready to study (and to design and study) strategies that nurture uses of research evidence that do better by children.

View the full-size figure in a new tab >

Nurturing Conditions

Theoretical and empirical research on the use of research evidence is remarkably consistent about what conditions facilitate research use across different policy contexts (e.g., education, child welfare, mental health, etc.) and spheres of decision-making (e.g., federal staffers, state agency leaders, district and school leaders, mid-level managers in many organizational contexts, etc.). I have conceptually placed these conditions into six buckets and reference a few examples for each:

- qualities of the available research

- relational infrastructure

- technical and logistical infrastructure

- mechanisms for knowledge exchange

- research evidence navigators

- trust.

Briefly, research use is conditioned by the research design of a study, as well as its perceived relevance, feasibility, and compatibility with decision-makers’ own theories of change (Bogenschneider & Corbett, 2021; Hyde et al., 2016; Mackie et al., 2016; Nakajima, 2021; Neal et al., 2018b; Olsen et al., 2024; Palinkas et al., 2016), with the latter factors being more salient.

The quality and structure of relationships within and across organizations shape research use (DuMont, 2015). Relationships affect access to ideas and findings from research, how that knowledge is valued, how it is shared, how it is interpreted, and how it is applied (Daly et al., 2013; Neal & Neal, 2019; Palinkas et al., 2016). High dependency on external consultants to support research use, for example, often limits internal efforts to deeply engage with and use research (D. Fettes, January 23, 2024, personal communication; Honig et al., 2017; Duff et al., 2023). Relationships can improve the consistency of resources available to support a research-use oriented system (D. Fettes, January 23, 2024, personal communication; Ahn et al., In press).

The size of an organization or institution, as well as its capacity, culture, leadership, and technical infrastructure, matter to research use in nuanced ways (Barnes et al., 2014; Chuang, et al., 2023; Neal et al., 2018a). Learning cultures that value research and provide a physical infrastructure, easy-to-use tools, and skill development to facilitate access to research or researchers are associated with higher levels of research use (Chuang et al., 2023; Farrell & Coburn, 2017; Honig et al., 2017; Neal & Neal, 2019; Wulczyn et al., 2016).

Advocates and other individuals and intermediary organizations are active agents of research and play an important role in research use (Posner & Cvitanovic, 2019). They interpret research and affect what knowledge is shared, with whom, whether it is used, and to what end (Gándara et al., 2017; Marin et al., 2018; Reckhow et al., 2021; Scott et al., 2017). They intentionally permeate boundaries of organizations and institutions, introduce vendors, and fuel movements (Gándara et al., 2017; Reckhow, 2021; Scott et al., 2017), yet are often not considered in the design of strategies to improve research use.

Research use requires routines, active learning, and supportive tools (Honig, et al., 2017; McDonnell & Weatherford, 2013; Metz & Bartley, 2020). Empirical studies consistently demonstrate a positive relationship between research use and active grappling with ideas and findings from research. This can take the form of debate, deliberation, or participatory methods (Boyko et al., 2012; Boaz & Metz, 2020; Coburn et al., 2013; McDonnell & Weatherford, 2013). These strategies appear to shift the value placed on research, users’ affective orientation, and internalization of ideas (Honig et al., 2017; McDonnell & Weatherford, 2013; Metz et al., 2022).

Trust is a central feature in research use (Asen et al., 2013; Bogenschneider & Corbett, 2021; Doucet, 2019; DuMont, 2015; Tseng, 2012). Trust matters in the relationships by which knowledge about research is exchanged, it matters when assessing the perceived qualities of research as an enterprise and with respect to study findings, and it matters when deciding to use research in the design of policy and implementation of practice that has the potential to affect children (Kirkland, 2019). Researchers are actively studying ways to engender trust (Metz et al., 2022).

In sum, there are ample resources to draw upon when designing and studying strategies to improve research use, even in the face of varied operating contexts and underlying conditions.

Conditions of the Operating Context

Studies on the use of research evidence make clear that the operating contexts that surround research use are busy places. They are stretched and stressed with competing demands and many knowledge resources of their own (Mackie et al., 2016; Palinkas et al., 2016). The italicized text highlights some of the expertise and evidence that is routinely generated and considered within an operating context alongside or in lieu of research. Studies on the use of research evidence also underscore that individuals and groups of individuals make decisions that may occur in the moment and are often iterative and unfold over time (Tseng, 2012). The operating contexts are inextricably linked to the broader environment (Small, 2022 and are influenced by values, politics, resource constraints, long-held assumptions and narratives, and knowledge from a range of sources (Scott et al., 2017).

Underlying Conditions

Underlying conditions affect every aspect of the research production, sensemaking, and research use ecosystem. These conditions are often structural in nature and affect what research ideas receive funding, which research findings are trusted, how research findings are interpreted, who advocates for or against the knowledge generated through research, the resources allocated for human infrastructure, and technological infrastructure that support use (DuMont, 2024).

Importantly, we cannot assume that the use of research evidence will have a uniform benefit (Kirkland, 2019). Earlier essays by Fabienne Doucet (2019, 2021) and David Kirkland (2019) describe the many ways the production of evidence can lead to harmful uses of research evidence; how systematic valuing and devaluing of different evidence generating methods can lead to harmful, incomplete, and erroneous uses of research evidence; and even how research evidence can be used to harm. These conditions are inconsistently attended to when studying research use, but certainly affect the question asked, the source of funding, the sensemaking, and the who, how, and what about research evidence is used (or not). Consistent with this observation, we encourage more explicit attention to the conditions underlying the research use ecosystem, and their interplay with and implications for nurturing conditions. This includes increased attention to the institutional cultures and political economy of research production and use (Georgalakis & Siregar, 2023; Miranda Samuels, 2022). For example, Ozer and colleagues (2020) are studying how evidence produced through youth participatory action research methods are used by administrators and staff in schools and school districts, which is not always seen as credible. The team is learning that active brokering with a focus on power is an important condition for acceptance of findings from youth-led research (Ozer et al., 2020). Further, they find that students benefit when the youth-led research about social-emotional learning is used to change the approach to and implementation of practice (Abraczinskas et al., 2022), and they are exploring strategies to better systematize opportunities to consider youth-generated research in school and district policy.

Part 4. Studying Strategies that Lead to Consequential Research Use

Since 2015, the Foundation has explicitly invited research studies that examine strategies to promote the use of research evidence in ways that benefit young people. Investigators have built and studied tools to promote the use of knowledge portals (Weber et al., 2023), make the values that inform decision-making more transparent (Hollands et al., 2019), and facilitated improvements to improve research-practice partnerships by attending to power dynamics (Ahn et al., In press). Given the many conditions that influence whether, how, and when research evidence is used, it is not surprising that most approaches for promoting research use are becoming more comprehensive. For example, rather than focusing on the quality and presentation of the research alone, some researchers are also restructuring relationships that already exist within an organization to build a learning culture that orients towards research as an aid and investing in technical infrastructure to make this engagement more routine. For example, Kimberly Becker and Bruce Chorpita (2023) are interested in the use of research to better support student mental health outcomes by improving student engagement in supportive services. They used methodically synthesized and curated related literatures to help identify the research base on contributors to engagement challenges and possible responses (Becker et al., 2015; Chorpita & Daleidan, 2009). They then embedded this rich knowledge base within a coordinated knowledge system for mental health counselors in schools, developed a protocol to orient school mental health clinical supervisors and their therapists to this research during supervision, and that activate many (although not all) of the conditions that support research use (Becker & Chorpita, 2023). They are evaluating the effectiveness of this coordinated knowledge system in a mental health system that is well resourced and had a tradition of using research evidence, as well as another mental health system that was less well resourced and experienced in order to understand how the operating context interacts with the research use strategy (Becker & Chorpita, 2023).

Max Crowley, Taylor Scott, and colleagues (2021a; 2021b) also adopted a multi-pronged structural approach to supporting collaboration between federal staffers, a coordinating hub, and a network of researchers to affect the use of research evidence in policy debates, guidance, and legislation, and researchers’ understanding and orientation toward policy-relevant research questions. Their strategy is informed by prior empirical studies on the importance of social networks in knowledge exchange, brokering, and the critical role trust plays in accessing, valuing, and using research evidence (Crowley et Crowley et al., 2021b). Further, they integrated work about the important role that deliberation and iteration play in making sense of research for a specific and local knowledge need and deep knowledge of the operating context (Crowley et al., 2021a). They designed and staffed a hub to broker the connection between federal staffers and a network of researchers who are on standby to synthesize relevant literature (Crowley et al., 2021a; Crowley et al., 2021b). They also trained researchers about the policymaking process to deepen their understanding of the operating context (Crowley et al., 2021a). They then randomized both staffers and researchers to examine the promise of these strategies (Crowley et al., 2021a; Crowley et al., 2021b). They also studied limitations of their approach, particularly as it related to underlying conditions, the researchers in their network, and the type of research that was to be shared with staffers (Long et al., 2021; Scott et al., 2022). In the next iteration of their research use strategy, they engaged in additional approaches to remedy observed challenges.

Research-practice partnerships also offer opportunities to activate multiple nurturing conditions while also deeply attending to the operating context and underlying conditions (Coburn et al., 2013; Farrell et al., 2023; Tseng et al., 2018). First, and as discussed above, relationships are critical for evidence use: relationships allow knowledge to be shared, interpreted, challenged, and refined (Daly et al., 2013). Second, research produced in partnership is more relevant to local contexts and is interpreted and used as such (Coburn et al., 2013; Honig et al., 2017). In part, the proximity of the researcher allows for deeper understanding of the operating context and underlying conditions (Finnigan, 2023). Third, engagement with the research process deepens understanding and research use (Farrell & Coburn, 2017). Fourth, research-practice partnerships can contribute to a consistent inflow of resources, which in turn can aid learning, technical system investments, and space for shifts in organizational routines and roles (Ahn & Gomez, forthcoming; Coburn, et al., 2020; Farrell & Coburn, 2017). But there are notable and repeating cautions (Farrell et al., 2021), including demands on time and the pull to remain in existing roles (Duff et al., 2023; Fettes, 2024, personal communication; Honig et al., 2017), as well as misaligned frameworks, resources, and power (Ahn et al., forthcoming; Shirrell et al., 2023). We recently funded two teams to contend with some of these challenges by directly attending to power dynamics (Welsh, grant October 2023) and embedding formal liaisons to managing the partnering (Turley, grant awarded October 2023).

Conclusion: Moving Forward with Intention to Use Research and Do Better by Children

Research can contribute to better child outcomes, but waiting for ideas and findings from research to make their way onto the desks of decision-makers is a flawed approach. We need strategies that intentionally nurture conditions that support the use of research evidence while also being mindful of underlying forces and operating contexts. This means strategies involving a single nurturing condition are likely insufficient. More comprehensive strategies and studies of those strategies are needed. Our Foundation invites studies that examine what strategies create these conditions, what mechanisms are operating, whether these strategies improve the use of research evidence, and ultimately, whether youth benefit from improvements in research use.

This work has tremendous appeal to those leading child welfare, education, justice, mental health agencies, and other youth-serving institutions, in addition to advocacy organizations. Foundation staff are frequently invited to engage with state agencies’ staff and leadership, professional organizations, advocacy organizations, and community groups who are keen to use research as they design policy, structure their organizations, and work with communities, families, and youth. Policymakers and those implementing policy want to know how they can build an organizational culture, allocate resources, and support staff in using research evidence to be more effective when working for and with young people. Yet we still lack the research that answers the questions of these interested parties. Thus, we look forward to reading your proposals for studies of strategies intended to improve the use of research evidence so that policy and its implementation can do better by children.

- For complete citations and references, download the PDF of this article.